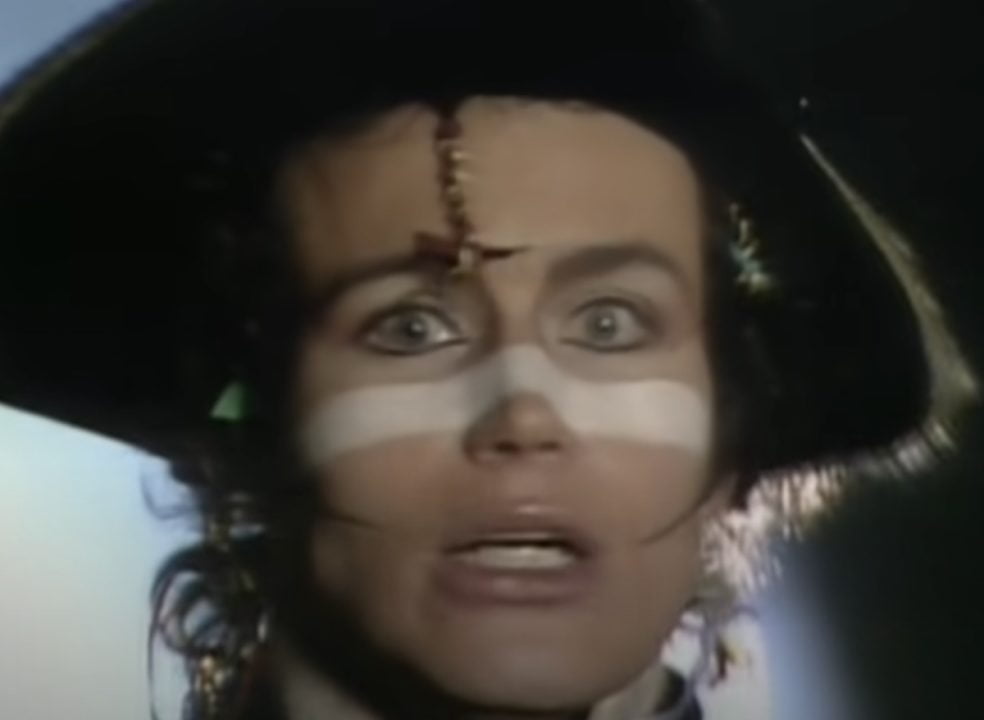

1981 saw Adam And The Ants becoming the biggest band in Britain. Merrick – aka drummer/producer Chris Hughes – tells Classic Pop of life inside the Ants during their rapid rise and equally sudden split…

“Adam told me ‘This is going to work. Six months from now, we’ll be household names.’ God bless him, we were on Top Of The Pops seven months later.”

After life as Merrick, half of Adam and the Ants’ dual drumming powerhouse with Terry Lee Miall, Chris Hughes instantly went on to be a hugely in-demand producer, helming records for Tears For Fears, Paul McCartney, Robert Plant and Peter Gabriel. Chris remains fond of his time behind the drumkit in the Ants, as well as getting his production break on Kings Of The Wild Frontier and Prince Charming.

Although the Ants split shortly after touring Prince Charming, by 1981 they were the biggest deal in town. Everything Adam Ant had dreamed of when turning his band from the arty punks of 1979’s Dirk Wears White Sox into proper pop stars had been achieved at an incredible speed.

If it’s hard to imagine a similar career progression now, it was just as unlikely in 1981. Even David Bowie needed a few years before and after Space Oddity to get it together.

For Chris, it was the intense bond between Adam and his writing partner/co-conspirator Marco Pirroni that propelled them onto the nation’s bedroom walls.

“Adam and Marco’s belief that the Ants would happen was very powerful and prevalent,” recalls Chris from his home studio near Bath. “They were like Mick‘n’Keith, those two. They were unbreakable and totally held up each other’s opinion. Adam and Marco were so tight you couldn’t pick either of them off, and their forward motion was unstoppable. It was ‘Yeah, I want this and I’m going to get this’ all the time.”

The unbeatable singles Stand And Deliver and Prince Charming were exactly what was needed to seal the Ants’ regal period as perfect colourful pop stars. Chris, albeit under his nickname, was cemented in 80s folklore in the chorus of Ant Rap.

“That ‘Marco, Merrick, Terry Lee…’ idea was just a joke,” laughs Chris. “It was very throwaway, something of an in-joke about the band mentality we had behind the image of Adam being the one in all the photos. It was chucked in for a laugh, typical of Adam’s humour, and it was something that we didn’t think would last beyond that week – never mind 40 years later.”

The fact people can recite the Ants’ line-up from muscle memory in seconds thanks to Ant Rap is typical of Adam’s Midas touch, an ability that developed as soon as the Ants’ pop line-up was assembled.

That came after the wreckage of the Dirk Wears White Sox band was famously stolen by short-lived Ants manager Malcolm McLaren, to form 14-year-old Annabella Lwin’s backing band in Bow Wow Wow.

Adam barely paused for breath before recruiting fellow punk face Marco as the ideal writing partner. Finding Chris was even more unlikely, as he’d had just one session as a producer before being tasked to rework existing Ants favourites Cartrouble and Kick as a single.

Chris had wanted to be a drummer for as long as he could remember. While banging a pair of drumsticks against tin cans playing along to records as a kid, he began picking out the same sonic elements a producer did, explaining: “I realised there was a lot of pop that I didn’t really like, yet the records still sounded fantastic. If you got players who were great, your record would sound a certain way, like Joe Meek’s stable of players. When I began playing drums at sessions, I was fascinated by what was going on in the control room – these guys nodding their head and talking away.”

Chris Hughes’ Ants story began when a friend asked him to help produce a session in Liverpool for early synth-poppers Dalek I Love You. Waiting to get the response from the band’s A&R back in London, Chris got chatting in reception to Ian Tregoning – head of Ants’ then-record label, Do-It. Ian asked Chris to send in a production demo.

“Three weeks later, Ian phoned to say, ‘I really didn’t like any of your tape, but I thought you were an interesting bloke,’” remembers Chris. “I was invited by Do-It to redo two Ants tracks. No budget, and I barely had any equipment.”

Chris used his nascent editing skills to reassemble the songs and, while handing the results over at Do-It, was startled when Adam burst in. “This was the week Malcolm had stolen the Ants from Adam,” he explains. “I’m certain Malcolm thought Adam would be overawed by Malcolm’s Svengali status and would kow-tow to whatever Malcolm thought Adam Ant should do. But Adam didn’t do that. Instead, he went ‘F*** the lot of you!’ in classically Adam fashion.”

Still livid at McLaren’s betrayal, Adam steamrollered Chris into producing new demos of the same songs. Chris says: “While I was talking to Ian about what I’d done on the new edits, Adam said to me ‘I don’t know who the fuck you think you are, but if you’re any good, why don’t you record me and Marco? If you think you’re any good, then let’s go, right now.’ That was on the Tuesday… and on the Friday we were in Rockfield Studios in Wales making Cartrouble.”

That session saw Adam double up on bass, with future Culture Club drummer Jon Moss acting as session sticksman. “I didn’t want to be the drummer as well as the producer,” insists Chris. “The burden of both playing with the Ants and trying to organise how they should sound as a producer didn’t seem feasible.

“I needed to be in the control room as a producer, which was arguably a safer place, to organise them and understand what the band was about. I could be more helpful in there. Certainly, my relationship with Adam was established as a producer, not a drummer.”

Read more: Adam Ant – The Albums

Read more: Adam Ant interview

Fate decreed otherwise, starting with Adam’s plans for the Ants’ distinctive dual drumming sound, drawn from Burundi in East Africa. “I knew the French field recordings Adam was referring to, where he’d discovered Burundi drumming,” says Chris. “The same as Adam, I loved the way the drumsticks click up on certain beats.”

Adam, Chris and Marco held auditions in Waterloo for prospective drummers, with Chris showing auditionees how to drum Burundi-style. Terry Lee Miall was quickly accepted, but Chris recalls a surprising number of other drummers failed to grasp the idea. At the end of the auditions, Adam turned to Chris and said “Oh, f*** it, why don’t you do it?”

The following day, Adam took Chris to a café where he outlined his vision for the Ants’ stardom, including his vow of how soon success would arrive. “I was cynical a couple of times in those early months,” admits Chris. “I thought ‘This is great, the energy talking it all up is fantastic, so let’s stick with it and not be negative.’ But I wasn’t sure, as much as I enjoyed Adam and Marco’s energy.”

The turning point arrived when the Ants played a tour in spring 1980 without having a record deal, including London shows at The Electric Ballroom and Empire Leicester Square. At a tour rehearsal for friends and family, “The room went nuts, says Chris. “I got the chills and it was so exhilarating it was exhausting.”

An A&R from CBS Records at the following Empire show was so impressed that he went backstage after just three songs to ensure he was first in the queue to sign what Adam and the Ants had become. “Every show was just chaos,” Chris laughs. “I had more than a suspicion then that it was going to happen, and it did. Everything just happened so fast.”

With that energy starting to pay off, just how intense was Adam Ant to produce?

“The great thing about Adam is that he wasn’t demanding at all,” reasons Chris. “He was aspiring, and there’s an important difference between that and being demanding. Instead of having the attitude of ‘Get me this, stop doing that’, Adam would say ‘I’d love this song to go like this. It’d be great if we could get the beat to do that.’ That meant you could try to sound just like it. Adam had so much positivity, you went along with him.”

Chris also cites Adam’s humour as vital to Adam and the Ants’ success, noting: “A lot of people don’t see Adam’s humour, although it’s evident in a lot of his lyrics, which are wry and tongue-in-cheek – like Ant Rap. Adam is very kind-hearted too. He’s a family guy, very considered and thoughtful. I’ve witnessed a lot of shades of Adam. I’ve seen him be difficult, but only because he was stressed and tired.”

Chris has no patience for those who try to belittle Adam because of his mental health struggles, saying: “I’ve always been on his team. So many people try to invite me to slag Adam off, saying ‘He was a mad one, wasn’t he?’ I won’t ever agree with that. The guy was an amazing artist.”

Although Adam and Marco fell out a decade ago, Chris is just as warm towards the Ants’ guitarist, having worked with Marco’s post-Ants band The Wolfmen. “I adore Marco and we speak on the phone a lot,” he enthuses. “Marco has a good take on most things in life. You’ll always get an amazing insight from him, whether it’s about music, fashion, design or art.”

As for Terry Lee Miall, he gave up music after the Ants ended, moving to California after meeting his American girlfriend and becoming a plumber. Chris believes he was the ideal partner in the Ants’ unusual drumming set-up, saying: “Terry knew I’d be calling the shots on the drums and he was always enthusiastic, going ‘Yeah, OK!’ He was very easy to work with, always buoyant and polite.

“We never had a cross word with Terry, and the only small issues arose on tour because he was quite anxious. We’d come off stage after a blinding gig and Terry would fret, going ‘Oh no, my drums sounded shit!’ We’d all tell him ‘They didn’t! They sounded amazing,” and Terry would then immediately be ‘Oh, right. Great!’ He’d go back to his usual enthusiasm really quickly.”

The Kings Of The Wild Frontier album stormed to No.1, with the title track and Antmusic both just missing out on becoming No.1 singles, the latter held off the top by Jealous Guy following John Lennon’s murder. Chris delights at learning of Mark Ronson’s love of his production on Dog Eat Dog, which the pop titan plays to new artists as the example of a perfect song to live up to. “I didn’t know that!” exclaims Chris. “That’s amazing!”

The producer is more aware of Adam Ant’s insistence to Classic Pop that one reason his singles did so well is because of his insistence that they start with an intro so explosive that Radio 1 DJs wouldn’t be able to talk over them.

“We had a conversation about how we enjoyed records that came on the radio as a call to arms,” explains Chris. “We wanted Ants songs to have that same feeling as, say, Fashion by David Bowie. They basically start by saying ‘Here we are, we’re going to be loud – check this out!’ That’s how the fanfare of Stand And Deliver came along, where you immediately want to go ‘Yes!’”

Read more: Adam Ant – Persuasion

Read more: Sigue Sigue Sputnik interview

There was no stopping Stand And Deliver and Prince Charming’s march to No.1 in the singles chart, but Adam has reservations about the accompanying album. While the enthusiasm of CBS Records’ A&R helped the Sony subsidiary sign Adam and the Ants, their brutal contract tied the band into delivering an album every year, or else another decade would be added to the band’s option. It’s no wonder that, after the whirlwind of actually succeeding as pop stars, Prince Charming is a little patchy.

“Adam is right, though we didn’t realise it at the time,” accepts Chris. “I’d also argue – and I think Adam would agree – that it’s the writing that was rushed, not the recording. I’m not suggesting Adam could have done any better under the time constraints we had, but if the writing had all been up to the calibre of the singles then Prince Charming would have been a much greater album. Once we were in the studio with the ‘record’ light on, the quality was still there.”

Having planned to be a producer happily lurking in the control room, what was it like to be part of a pin-up band? “Gruelling!” responds Chris. “It was a chaotic time. We’d be on tour in Sweden, get told we’re No.1, so we’d fly back to do Top Of The Pops and fly straight back to Spain where the tour was now meant to be.

“It took its toll and there wasn’t anyone to tell us ‘This is chaos now, but it’ll be great soon, because we can slow it down and take more time next time.’ There was a general undertone in the Ants that we had to grasp it while we can. There was a lot that happened in the Ants that I didn’t expect, and I maybe sleepwalked into it because of Adam and Marco’s drive.”

Chris also believes the pressure hid Adam’s mental health concerns, commenting: “Adam seemed to feel OK in that chaotic world of success. If you’re in that bubble of mayhem and chaos with everyone else, no-one is aware of your own turmoil, because it’s just part of the bigger chaos.”

The end of Adam and the Ants soon resulted. Adam has since told Classic Pop he believes the band could have lasted longer if they’d had a break. Chris agrees, but points out: “Maybe we could have integrated Adam and the Ants around Adam pursuing acting and whatever else he wanted to do in addition to the band.

But managing his own career was tough enough for Adam. Managing his own career and that of the band, while we were all starting to have our own ideas, would have been really tough.”

Instead, Chris was tipped off about the band’s split after Adam took him out to lunch to say: “I’m ending the Ants, but Marco and I would like you to continue as producer.”

Chris produced Goody Two Shoes – famously credited to Adam and the Ants – but then got invited to work with a friend’s young band in the west country, Tears For Fears. “I would have carried on producing Adam,” ponders Chris. “I knew how to make Adam’s songs work, but I was seriously into producing by then. I certainly didn’t want to be an Ant or a lived drummer anymore, it made much more sense to try to be a producer.”

Adam and Chris stay in touch via text, always chatting on Adam’s birthday. Would Chris produce Adam Ant again? “The paperwork would have to be right,” cautions Chris. “If it was, then yeah, I probably would.” Merrick and Yours Truly might just have more adventures in store.

Check out Adam Ant’s official site

Read our feature on the making of Blondie’s Parallel Lines

Classic Pop may earn commission from the links on this page, but we only feature products we think you will enjoy.